Oh, Thanksgiving. A bad day for turkeys, most everywhere. There are loads of jokes talking of the turkey’s demise.

“What did the turkey say to the turkey hunter on Thanksgiving Day?”

“Quack, Quack!”

Heck, the President even pardons a turkey every year. Reportedly, that turkey gets to live out a full life, dying eventually, of natural turkey causes.

But there’s more to the bird than meets the eye. The turkey is fairly new, in the way of fowl. Turkeys evolved about 100 million years ago, from some kind of little flying dinosaur. But chickens, those crazy chickens, had them beat by a long shot.

The chicken’s early beginnings came from a group of dinosaurs called the theropods. They evolved into two categories, some 230 million years ago. The names of the groups are crazy, but here they are. Ceratosauria and the Tetanurae. The Ceratosauria was the same genetic line that produced the Tyrannosaurus rex. So when you eat chicken, you are having T-Rex, sort of.

I don’t know which dinosaurs ended up being cousins with the turkey. But I know quite a few humans who could be related.

Anyway, turkeys nearly went extinct. We almost hunted them to death, literally, in the 1900s. The population reached a low of around 30,000 birds. But someone was thinking and developed restoration programs across North America. Today, we have about seven million birds.

Now here’s a thing. There are six subspecies of wild turkey, all native to North America. During that first Thanksgiving, those hungry pilgrims hunted and ate the eastern wild turkey, M. gallopavo silvestris.

That line, the “Galloping Sylvester” line, has a range that covers the eastern half of the United States and goes well into Canada. These turkeys are sometimes called the forest turkeys. This is most likely the kind we see in the wild, as they are the most numerous of all the turkey subspecies. Every so often, we will see a wild turkey on our property, and it makes us happy. The last time I did a head count, the forest turkeys numbered more than five million.

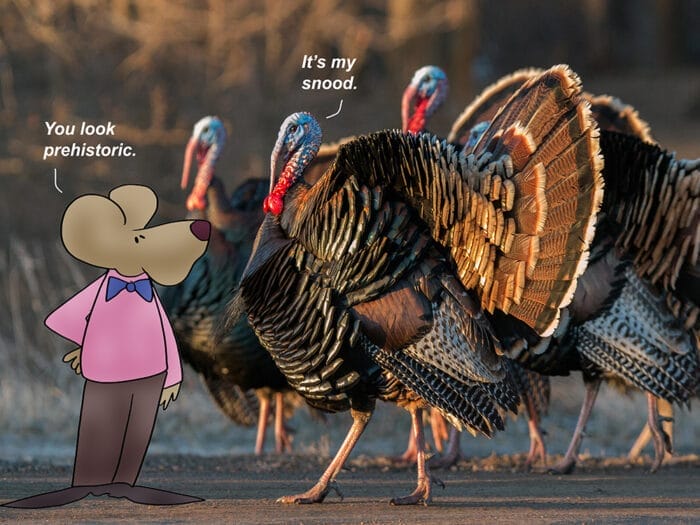

Okay, so why do they have the red, fleshy, dangly thing on their faces? First off, it is called a snood. Yes, a snood. It is a “macho meter” if you ask me. The snood functions in two ways. Female wild turkeys prefer to mate with long-snooded males. The bigger the snood, the better. And. If two boy turkeys are hanging out together, deciding who gets to control the clicker? Male turkeys defer to males with relatively longer snoods.

Not to be confused with their wattles. That’s the red fleshy piece right below the chin.

So if this interests you, and you want to know the difference between a male and female turkey, feed them, and wait. Boys produce spiral-shaped poop, and the girls poop in a shape like the letter J.

But there is more to their drumsticks than the meat. I think, this time of year, we should have National Turkey Races. Turkeys are fast and can run at speeds of up to 25 miles per hour and fly as fast as 55 miles per hour. We could have categories. There could even be a longest snood contest.

Turkeys, most of all, love their family and friends. They do a roll call in the mornings. When they are allowed to live in nature, turkeys like to sleep in trees with their extended family flocks. Being up in the trees keeps everyone safe from predators. And when daylight comes? When they start to wake up in the morning? One turkey will call out a series of soft yelps to make sure that the rest of the group is alright since they haven’t spoken to one another overnight.

Happy Thanksgiving. I hope you and all your extended families are all alright.

============

“Let us remember that, as much has been given us, much will be expected from us, and that true homage comes from the heart as well as from the lips, and shows itself in deeds.” – Theodore Roosevelt

===========

“Gratitude unlocks the fullness of life. It turns what we have into enough, and more.” — Melodie Beattie

==========

“I come from a family where gravy is considered a beverage.” – Erma Bombeck

==========

If you poop in the shape of the letter J, your snood doesn’t matter.