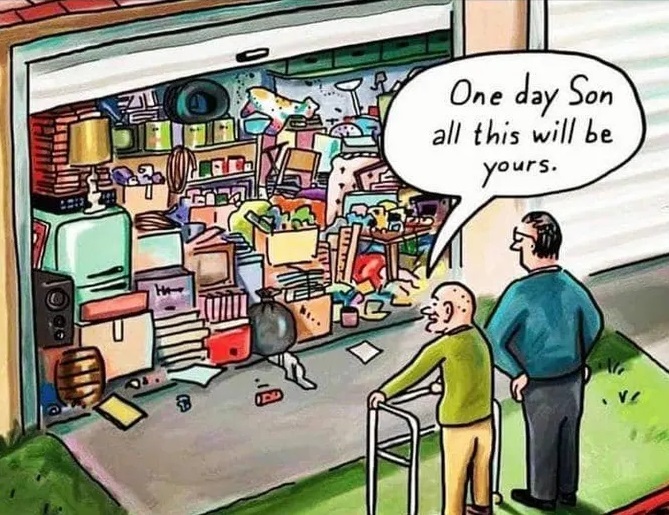

Lots of notable people died on this day.

I wonder what kind of “stuff” they left behind.

Did they live a life of austerity? Or did they accumulate loads of possessions?

Like these guys, all of them passing away on an October 5th, somewhere in time.

General Charles Cornwallis 1738-1805 — Neat as a pin.

Tecumseh ??-1813 — Clean teepee.

Rodney Dangerfield 1921-1904 — Packrat.

Steve Jobs 1955-2011 — Shiny Apples.

I’m just guessing about each one of these men. But one thing is for sure. They left some possessions behind.

In today’s blog, my good friend and excellent writer, Linda Stowe, addresses that very topic.

____________________________

In Plain Sight

by Linda Stowe

My friend Michael’s dining table is mounded with piles of mail he hasn’t opened in… well, years. A former co-worker Sylvia had two bulletin boards that were covered with a kaleidoscope of colored slips of paper reminding her of important tasks that she often forgot. Another former co-worker, Tom had an immaculate office so spartan you’d think a monk worked there. Until you opened a drawer or cabinet and masses of paperwork spilled out.

My friends Michael, Sylvia, and Tom all were oblivious to their clutter. To Michael, it was part of the furniture. To Sylvia, it faded into the background. And to Tom, it was out of sight, out of mind. I saw it every time I entered their space and so did anyone else. But to Michael, Sylvia, and Tom it was invisible. They saw it every day until eventually they no longer noticed it.

I have been thinking about my friends lately because I have begun another round of death cleaning. Don’t be alarmed, no writers died in the production of this piece. I got the term “death cleaning” from a little book I read, The Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning: How to Free Yourself and Your Family from a Lifetime of Clutter by Margareta Magnusson. Death cleaning is based on the idea that it is better to deal with the emotional and practical aspects of decluttering while you are still alive, so that your loved ones do not have to do it after you are gone. Anyone who has had to deal with a relative’s belongings after they have passed will understand the dilemma of dealing with belongings that carried great meaning to their loved one but not to those left behind.

Death cleaning has become so popular because we are living longer, and we all tend to accumulate too much stuff. There are books and videos about decluttering. There are seminars and myriad methods of tackling the problem. There is even a TV series. I belong to a Facebook group that includes posts such as the one from the woman who lives in Denver but still rents a storage locker in New Jersey containing her deceased mother’s quilt collection and dinner service for 12. Or the woman who wondered whether her son would like the jar of his baby teeth that she has saved all these years. Michael’s dining table piled with mail doesn’t sound so bad now, does it?

From my considerable research on the topic, you might think that I am a packrat whose home is filled with plastic tubs of craft supplies, piles of National Geographic magazines, and stacks of clothes I haven’t been able to wear in decades. It is not. I am basically an organized and tidy person. But I do have more stuff than I want to pass on to my family. I have been death cleaning for about ten years now, but I still have a few things to tackle. I still have too much paperwork (e.g., service records of cars I no longer own), too many socks (I’m embarrassed to say), and goodness knows what still lurks in that front closet.

From my experience in organizing, I leave you with three tips: 1) Tackle things in small increments. I devote only 30 minutes to the task once a week. Not overwhelming, but over time my progress is evident. 2) Start with something that is easily sorted and is not sentimental. You’ll make faster progress if you go through your sock drawer than if you sort through family photos. Save the emotion-laden stuff for last, but maybe herd it into its own little area. 3) Have a strategy and be consistent in your effort. My strategy is to have as few belongings as necessary while still maintaining my comfort. That comfort includes keeping a few personal possessions that I enjoy. To stay consistent, I don’t over-commit myself to the project – 30 minutes, once a week. And I enter it as a “to do” on my weekly calendar. I know there will come a point when I cannot manage those 30 minutes and I’ll be glad for all those other times when I did.

========

(Editor’s Note: The image is not one of Polly’s original works. The source is unknown.)