We know him as Ulysses S. Grant, the great Civil War General and 18th President of the United States. But his real name was Hiram. Nonetheless, he died on this day, July 23, 1885, of terrible throat cancer.

Hiram Ulysses Grant was born in Point Pleasant, Ohio, on April 27, 1822, to Jesse Root Grant, a tanner and merchant, and Hannah Simpson (no relation to Homer or Bart). He was the oldest of six children, and little Hiram started school at the early age of five. Eventually, though, he went to work in his father’s tannery. Hiram did not like it, one bit.

So, in 1839, Hiram Grant, at age 17, went to the United States Military Academy at West Point. Upon arrival, he found that he had been wrongly registered as “Ulysses S. Grant.” He probably said, “But my name is Hiram.” And they told him it didn’t matter what he or his parents thought. The paper on the desk said his name was “Ulysses S.” It was government-official and could not be changed. So the name stuck.

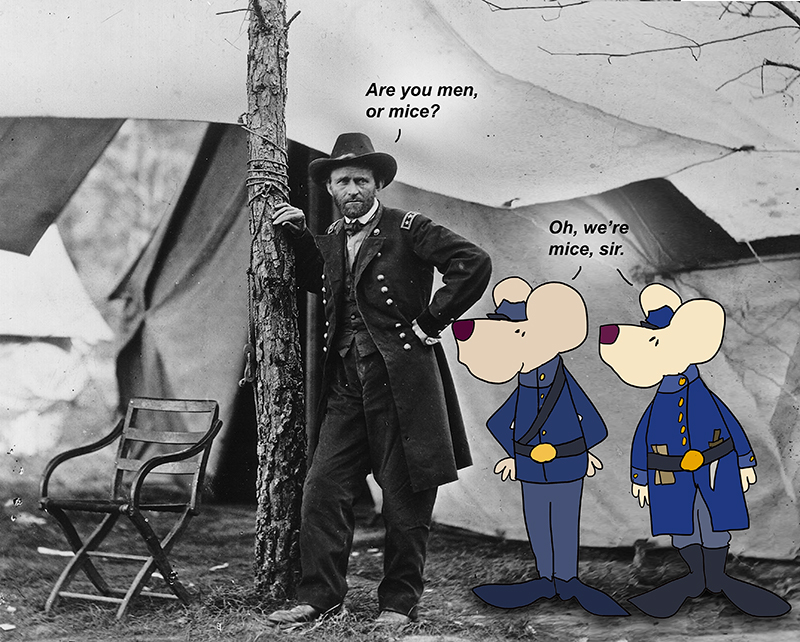

Grant became a general at the start of the American Civil War and then the leading general in the Union Army from 1864 to 1865. His wartime achievements made him a popular figure in America. This definitely helped him to win the presidency in 1868.

He did some pretty nifty things when he was in office, like stabilizing the post-war economy. He also created the Department of Justice, and appointed African-Americans and Jewish Americans to prominent posts. Another good measure came when he initiated prosecutions of the Ku Klux Klan.

Grant was re-elected for a second term in 1872. But there were some things happening that would catch up with him. From the start of his presidency, Grant had a tendency of appointing friends into high political positions. (Sounds a little familiar.). And, in spite of this, or because of it, his administration had become riddled with bribery, corruption, and fraud.

Grant, himself, remained honest, even though he drank entirely too much. But, appointing government officials based on friendship rather than worthiness left him with a weak administration. (This still sounds familiar to me.).

His time in office sunk to its lowest after Grant appointed John MacDonald, as an Internal Revenue Service supervisor. John MacDonald had been an old army buddy. Old MacDonald. Anyway, he became responsible for what became known as The Whiskey Ring. It was a huge undertaking, a scandal that involved massive fraud and tax evasion.

Here’s how it went down. By bribing officials, whiskey distillers were able to pay tax on only a small portion of their production. As such, they were cheating the government out of millions of dollars a year. MacDonald, of course, kept some of the money for himself. But the low-down, dastardly part? MacDonald told friends that Grant was in on the fraud.

Rumors spread. Things got messy. So, Grant’s Secretary of the Treasury, Benjamin Bristow, launched an investigation. And, Grant told him outright: “Let no guilty man escape.”

The result? In 1875, MacDonald and more than 350 distillers and government officials were indicted. MacDonald went to jail. But it was proof enough for most Americans that Grant’s administration was corrupt. And he was guilty by association, of course.

He made his apologies before leaving office, but the public didn’t care. The New York Sun described Grant at the time as “the most corrupt President whoever sat in the chair of Washington.”

His life did not get better after leaving office. In 1884, he found out that a corrupt partner in his Wall Street brokerage firm had been running a pyramid scheme. Everything went bust. Grant’s investment firm collapsed, and his life savings were gone.

He later told a friend: “When I went downtown this morning, I thought I was worth a great deal of money. Now I don’t know that I have a dollar.”

And just when things seemed to be at their lowest, another blow came. In October of 1884 he had a horrible sting in his throat. He was diagnosed with an incurable throat and tongue cancer, probably brought on by his habit of smoking several large cigars every day.

So, there he was, penniless. And he couldn’t bear the thought of leaving his wife Julia a destitute widow. As sick as he was getting, Grant contacted his friend Mark Twain. Twain had urged Grant for years to write his memoirs. Even though Grant was very reserved, he could tell a great story. He had a way of entertaining Twain and others with stories of war and politics.

So he started writing. Grant began producing a remarkable 10,000 words a day. He pressed on through illness, even though he could not eat solid food or barely swallow.

Doctors treated him with morphine, cocaine, and injections of brandy. Finally, after producing a massive 366,000 words in less than a year, he stopped work on July 16, 1885.

He died a week later.

Mark Twain must have been a great pal. After Grant’s death, he organized a massive door-to-door sales campaign. Mark Twain sold more than 300,000 copies of the two-volume Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant. (It outsold Huckleberry Finn, even.)

Julia Grant received a total of $450,000 in royalties – equivalent to $12 million today.

And today, assessments of his presidency have also improved. He was once thought to be the worst, but now, looking back, historians ranked him 21st in the presidential list. (Trust me, we’ve seen MUCH worse.)

Today marks his death. A challenging life. May he always rest in peace and good spirit.

========

“Courage. Kindness. Friendship. Character. These are the qualities that define us as human beings, and propel us, on occasion, to greatness.”

― R.J. Palacio, Wonder

========

“…Next time you’re faced with a choice, do the right thing. It hurts everyone less in the long run.”

― Wendelin Van Draanen, Flipped

=========

“Human happiness and moral duty are inseparably connected.”

― George Washington

=========

Who’s buried in Grant’s tomb?