Okay. Hold on to your wooly hats because I have something to tell you. It was on this date, May 24, 1830, that the renowned poem, “Mary Had A Little Lamb,” was first published by Sarah Josepha Hale (with the Boston firm Marsh, Capen & Lyon).

But wait. There’s more.

Let’s start with Sarah Josepha Hale. Her birth name, Sarah Josepha Buell, was born — on October 24, 1788 — in Newport, New Hampshire, to Captain Gordon Buell, a Revolutionary War veteran, and Martha Whittlesay Buell.

Her parents were progressive people, and as such, they believed in equal education for both genders. So, little Sarah was home-schooled by her mother and elder brother Horatio, who had attended Dartmouth. They say that otherwise, Hale was an autodidact — a self-taught person.

Young Sarah Buell grew up and became a local schoolteacher. As young women do, Sarah met a lawyer named David Hale in 1811. It sounds like they fell crazy in love, and the two of them were married on October 23, 1813.

Oh, they got busy too and had five children: David (1815), Horatio (1817), Frances (1819), Sarah (1820), and William (1822). I’m not sure how it happened, but nine years after they were married, her loving husband, David, died in 1822.

She missed him. Sarah wore black for the rest of her life as a sign of perpetual mourning. Spoiler alert. She lived to be 90. That’s a lot of years and a lot of black dresses.

Back to the story. She turned to her poetry writing as a way to support the family. Her most famous book, titled “Poems for Our Children,” included a good story. “Mary Had a Little Lamb.” As we know, it became quite popular.

But here is where the controversy comes in. That little story? It turns out, this encounter happened to Mary Elizabeth Sawyer, a woman born in 1806 on a farm in Sterling, Massachusetts. In 1815, Mary, then nine, was helping her father with farm chores. They discovered a sickly newborn lamb in the sheep pen, and the darn thing had been abandoned by its baaaaad mother. So Mary wept and pleaded with her Dad, as kids do, and the guy broke. He let Mary keep that little lamb, whose fleece was white as snow. Her father didn’t hold out much hope for its survival. But we know how love can be. Against the odds, Mary managed to nurse the lamb back to health.

The true story pretty much follows suit. Mary and her siblings went off to school one day, and the lamb started following them. As hard as she tried, she couldn’t get it to stay put. So the lamb went to school, and Mary hid it under her desk, covered with a blanket. When Mary was called to the front of the class, the lamb popped out, and everyone had a good laugh. The lamb had to wait the rest of the school day outside for little Mary.

The next day, one of her classmates, John Roulstone, wrote a poem for her. That poem. The Mary Had a Little Lamb, poem. This was 1815. It was 1830 when Hale published “Poems for Our Children,” which included a version of the poem.

According to Mary Sawyer, Roulstone’s original contained only the three stanzas, while Hale’s version had an additional three stanzas at the end. Mary said she had no idea how Hale had gotten Roulstone’s poem. When people asked Hale how she got a hold of it, she said her poem wasn’t about a real incident but rather something she’d just made up.

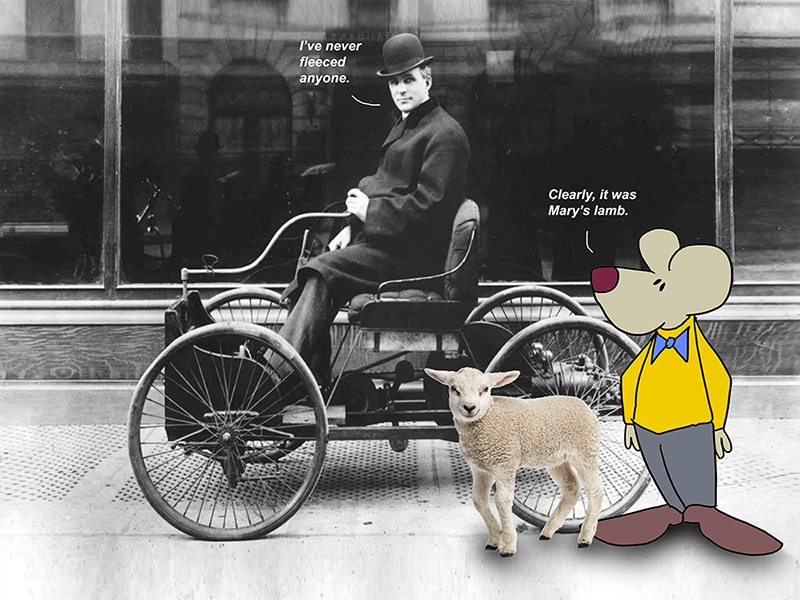

Soon the residents of Sterling, Massachusetts, and those of Newport, New Hampshire, where Hale hailed from, were arguing about the poem’s true origin, and this argument continued for years and years. In fact, in the 1920s, when both Mary and Sarah were dead and gone, none other than Henry Ford, the man who made the cars, got involved in the dispute. The inventor sided with Mary’s version of events.

He ended up buying the old schoolhouse where the lamb incident took place and moved it to Sudbury, Massachusetts. Then, he published a book about Mary Sawyer and her lamb. I don’t know why he got involved in this. Maybe he counted sheep at night to sleep.

Regardless, in the end, it seems most likely that Hale simply added the additional stanzas to Roulstone’s original, which she had come across, somehow.

Everywhere, that lamb was sure to go.

=========

By doubting we are led to question, by questioning we arrive at the truth.

— Peter Abelard

=========

All truths are easy to understand once they are discovered; the point is to discover them.

— Galileo Galilei

==========

It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.

— Antoine de Saint-Exupery

===========

Whose fleece was white as snow, but the story isn’t.